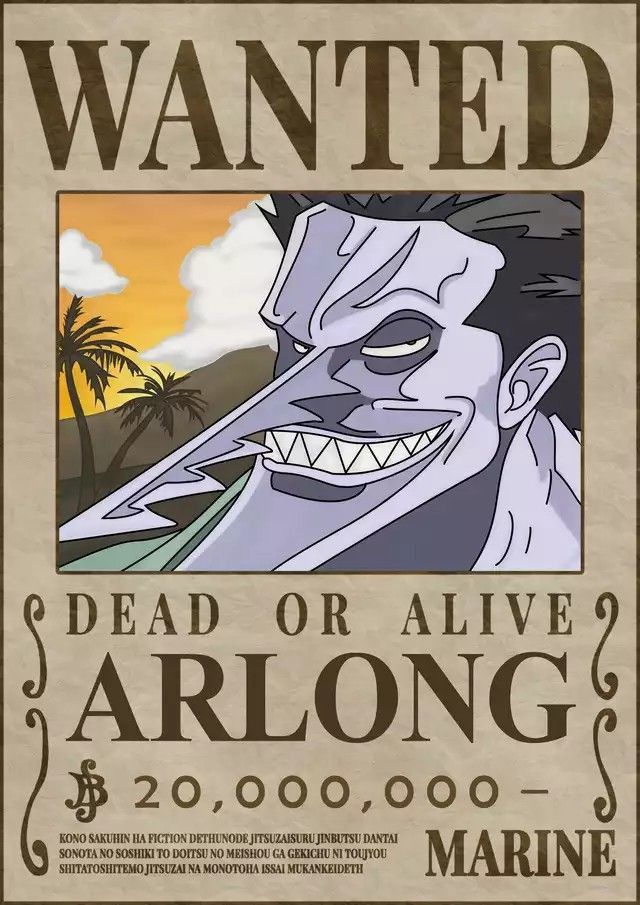

Behold, Arlong the Saw.

Long considered one of the first landmark villains of One Piece, Arlong casts a long shadow across the history of Oda’s pirate epic. In spite of appearing in only two significant story arcs and last appearing in the pages of Jump over a decade ago, he remains a formidable figure in Luffy’s rogue’s gallery. There are many reasons for that.

The first is the most obvious, which is his striking physical appearance. Oda isn’t known for his standard character designs but Arlong is extreme, even for him. The serrated nose and wild, glaring eyes makes the Fishman captain uniquely memorable, so much so that when his sister appears, a decade after Arlong’s last appearance, their shared pupils made it immediately obvious to most that the two characters were related.

Arlong’s physical stature is significant in no small part because of how closely tied it is to his other memorable characteristic – his bigotry.

The pure contempt Arlong holds for human beings comes from an obvious source. As a fishman, he is bigger, stronger and tougher than a human and he can breathe underwater to boot. He routinely demonstrates all those qualities to keep the people who pay him tribute in line. When they don’t pay up he feels no qualms in destroying their livelihoods or ending their lives in order to serve as an example to others. Why should a fishman care for the lives of humans, after all?

Arlong’s insistence on categorizing people by species eventually sets him at odds with the protagonist of One Piece, Monkey D. Luffy. Luffy is unable to grasp why human or fishman are such important categories to Arlong. However, as is often the case, Luffy would have been perfectly happy to ignore Arlong’s ugly prejudice and brutal regime if not for one little detail.

Luffy was trying to recruit a member of Arlong’s crew. The only human member, in point of fact.

Yes, as odd as it sounds the crew known as the Fishman Pirates had a bonafide human girl serving as their chief cartographer and navigator. Arlong brought on the orange haired girl when she was only eight. Nami offered to serve Arlong after the fishman murdered her mother, on the condition that Arlong would allow her to buy back her village for the measly price of 100,000,000 beri, the world’s standard currency. (For those wondering, that’s the rough equivalent of $1,000,000 USD circa the year 2000.)

Luffy meets Nami when she’s in the process of robbing another pirate crew and eventually follows her all the way back to Coco Village and the eventual showdown with Arlong. For the entirety of the storyline, we’re primed to hate Arlong. This is a carefully balanced thing on Oda’s part, because the story goes to great pains to make it clear not all fishmen are like Arlong. In particular, Oda introduces us to the character of Hachi, Arlong’s first mate.

Hachi is a very likeable character. He’s cheerful, helpful and never demonstrates any of the overt prejudice that so clearly defines his captain. He just seems to like people until they give him a reason not to. In this respect, he’s not that different from Luffy. However, Hachi is agreeable to Arlong’s bigotry, so he’s not perfect by any stretch of the imagination.

Yet Hachi is important. Of all the characters introduced in the Arlong Park he is the only one Luffy will meet again.

For the next seven years, more or less, of One Piece’s publishing history very little happens to change our mind about fishmen. We only meet one who isn’t a villain. We meet several more we don’t really care for. Then the Straw Hats arrive at Sabaody Archipelago, an anchorage on the doorstep of Fishmen Island, and they run into Hachi again.

They find him in a cage. He has been captured by human traffickers, who are using him as bait to capture prisoners for a slave auction. This, we learn, has been the fate of fishmen for centuries.

Sabaody Archipelago tells us a lot about the state of the world but for our purposes the most important thing it tells us is the fate of the fishmen. Arlong’s hatred for humanity was ugly and evil. However it sprung up from a fertile soil of other evils such as slavery, ostracisation and dehumanization. That context opens us up to a new understanding of the fishmen we’ve seen before. It prompts Nami to forgive Hachi for his role in Arlong’s pirates. And, ultimately, when we arrive on Fishman Island, it prepares us to hear the story of Fisher Tiger.

The great explorer Fisher Tiger is one of the heroes of Fishman Island and he stands in sharp contrast to the other major figure his story is intertwined with, Queen Otohime. However, in order to understand the crime of Fisher Tiger she is unimportant. So I plan to set her half of the storyline aside and those curious about it can read it at their leisure. They are quite separate stories, for the most part.

What is important to understand about Fisher Tiger is that he lived and died in the past. Luffy and the Straw Hats hear his tale from Tiger’s first mate, a fishman named Jinbei. Among the fishmen, Fisher Tiger is a legend. He united the forces of Arlong and the Fishman Pirates with many powerful warriors from the Ryugu Kingdom, Jinbei first among them, to create the Sun Pirates. Then he dedicated his life to raiding ships and freeing slaves.

To Fisher Tiger, the species of slave did not matter. Slavery was an equal opportunity evil and both humans and fishmen suffered from it. And Tiger was a man particularly suited to recognizing the evil of it, as Tiger himself had suffered the humiliation of being a slave. He was wise enough to see that freeing every slave would create a larger push to abolish the institution than just freeing a few. So he fought against all slavers, although the fishmen may have benefited most from it.

At the same time, Tiger forbid his pirates from senseless killing. While fighting carries the risk of death Tiger knew that any killing beyond that would undo all the work he was doing towards abolishing the system and set fishmen and humans at odds for decades to come.

The combination of these two strategies made Fisher Tiger very effective.

Unfortunately, it only made him effective in creating pressure to abolish slavery, it did not do much to improve the reputation of fishmen in the wider world. This would eventually lead to his downfall. When not hunting slavers and freeing slaves the Sun Pirates would help liberated slaves find their way home. When they freed an eight year old human girl named Koala they naturally set out to do so.

However, Koala’s home village was fairly far inland. The whole crew couldn’t go with her, so Fisher Tiger took her there himself. Once Koala was reunited with her family Tiger headed back towards the sea but along the way he was ambushed by Marines.

The people of Koala’s village had notified the World Government there was a fishman in their town and they showed up to arrest Tiger. When he refused to surrender they opened fire. Tiger managed to escape this ambush but he was badly wounded. The Sun Pirates were also attacked and lost their ship but managed to capture the Marine ship instead.

Most of the Sun Pirates were fine but Fisher Tiger needed a blood transfusion to survive. The Marine ship had plenty of blood in stock in the sickbay but when it was offered to Tiger he screamed, “No! I would rather die than have their blood inside me!”

In the end, Fisher Tiger lost his long battle against the hatred he had harbored and died saying, “It’s foolish to die and leave only hatred as a legacy. I know that! But my reason is overpowered by the demon in my heart… I cannot love humans. Ever.”

At that moment this was Arlong the Saw.

At that moment, he was me.

After escaping Marine custody due to the influence of his crewmate Jinbei, Arlong would set sail for the eastern oceans with a bone in his teeth. He would take his vengeance on the humanity of those seas, saving his cruelest treatment for an eight year old girl he found begging for the freedom of her village.

Thus the circle closes and we see the full weight of the evils that had piled up. Arlong was just one final stone in the ever growing pillar of prejudice, hatred and abuse that had been building and building over generations. Yet he might not have been as vile if he hadn’t watched his captain try to break that cycle and fail. If the cycle hadn’t looked so inevitable perhaps even Arlong could have been someone different.

The crime of Fisher Tiger wasn’t that he tried to change the world and end slavery. It was that he tried to change himself and couldn’t.

Around these parts I have a simple concept. That the goal of art is to create an emotional response in the audience. If you are telling a story, try to make the audience share that emotion with a character in the narrative. I call this emotional synchronization.

This storyline, what I call The Last Crime of Fisher Tiger, is buried in four larger story arcs told across a dozen years of publishing history. It is one of the greatest examples of the power of emotional synchronization I have encountered. Through the use of it Oda showed his audience a person they despised.

And let me tell you, we despised Arlong in those days.

Then, over time, Oda gradually maneuvered the audience until we experienced an overwhelming wave of sympathy for Arlong when we saw him heartbroken by Fisher Tiger’s death. This moment was quickly tied back to the Arlong we saw torture Nami, creating a powerful dissonance in the audience. Never have I seen a moral message so seamlessly integrated into a story with such clarity.

Anyone can say, “You, too, would be a monster.”

To take the hand of the audience and slowly and patiently walk them through the path that would make them a monster demands incredible skill. Many writers today wish to tell morality tales. Yet so many of those who attempt it fail miserably. Fisher Tiger is a powerful model they would do well to learn from.

But that isn’t all they should learn from.

After the death of Fisher Tiger a strange custom takes root in the Ryugu Kingdom. The fishmen there refuse to share their blood with any human who passes through their ports. The kingdom isn’t strong enough to directly defy the World Government and this becomes their way of protesting.

In modern times the Ryugu Kingdom is not a peaceful place. Luffy takes up their cause and fights on their behalf, doing much to warm the hearts of Fishman Island towards humans. But things don’t end cleanly. Luffy suffers quite a bit in the battle and at the end he’s in danger of bleeding out. His own crew doesn’t match his blood type. Yet none of the fishmen he’s just saved will help him.

So it falls to Jinbei, Fisher Tiger’s first mate, to break the custom and offer his own blood to Luffy. When Luffy recovers he finds himself linked to Jinbei in more ways than one. So he smiles and says, “Jinbei, join my crew.”

With that, for the first time in centuries, the wound is closed and the crimes of Fisher Tiger are redeemed by his successor. The dawn of the world grows a step closer, and we raise our sails with hope once more.