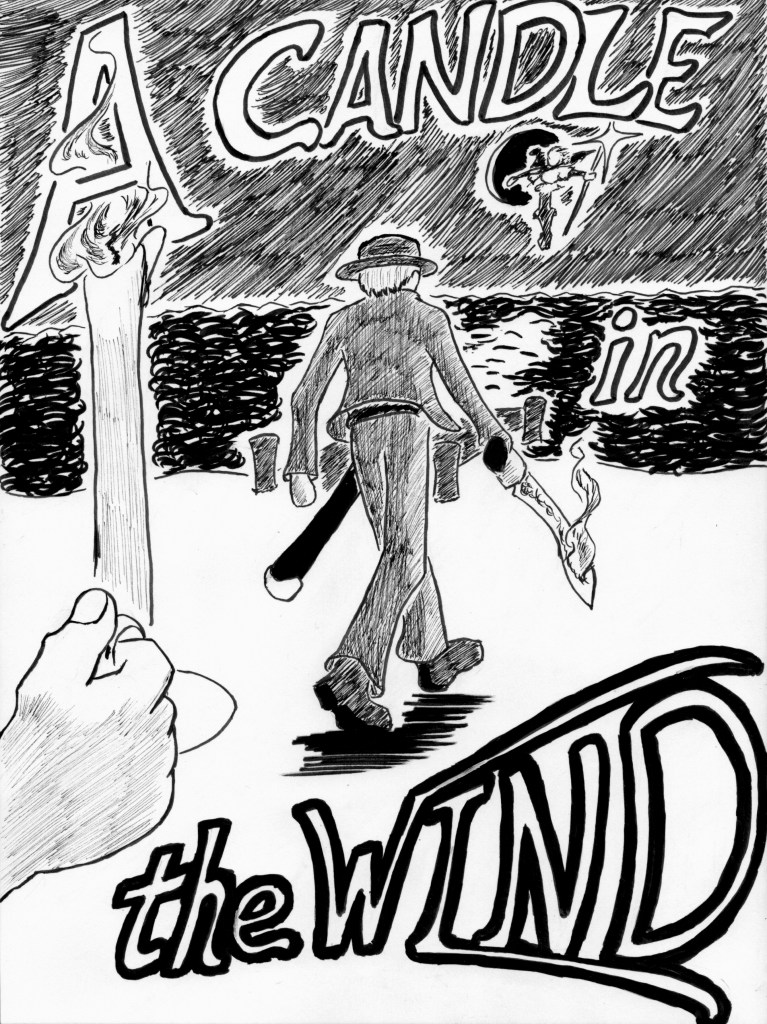

At the beginning of the year I set myself a number of writing goals, one of which was to document and share my own process of writing. During the writing of A Candle in the Wind I took a few notes beyond the normal. Now I share the outcome with you, in the hopes that there is something here that can help the writer looking to refine their own process. This is just what I’ve found works best for my own writing. I encourage anyone trying to streamline their own writing process to experiment. There’s no guarantee any of this will prove helpful but creative writing is one of those things where you don’t really know if a technique will fit you until you try.

Note that the point of this isn’t to tell you how to come up with an idea, premise, characters or setting. This is about how you turn those things into a story. So in writing this I’m going to presume you have all that stuff worked out already and talk about how you arrange those things into a narrative.

The first thing I do is outline my story.

A lot of people say that outlining takes spontaneity or life from your story. My understanding from what they describe is that they feel shackled by their outline and cannot depart from it once they’ve written it down or the story feels listless if written from an outline. These are both the result of mindset, I believe. Some people want to explore their narrative as they write it and then just tweak and refine the narrative once they have it all down. Others lose interest in the story once they have all the beats worked out.

While neither of these are an innate shortcoming of outlining your story if you find either of these things to be the case outlining is not likely to be a helpful technique for you. Fighting that bent in your personality probably isn’t worthwhile. Everyone creates differently and it’s better to lean into your own proclivities than to try and contort your own thought processes to a particular technique. But if neither of these are the case I strongly suggest outlining as a huge time saver before you get into the meat of your story.

The point of an outline is to establish a structure and check for major contradictions before you spend hours typing out early chapters. In general I try to lay out between 15 and 25 basic plot beats I want to take place. Some outlining guides suggest including “up” or “down” in your beats but that is not something I do any longer, although I did try it at one time.

Once I have the beats laid out I work backwards, checking if I need to set up anything early on that will pay off later in the story. I also look for beats that contradict each other. Once the outline is written I leave it for two or three days then reread it with fresh eyes, looking for contradictions and asking if I like the story. In general the beats get rewritten 4-5 times. For an idea of what the finished product looks like, here’s the final outline from A Candle in the Wind.

- Roy is in the jail of Riker’s Cove, watched by Sheriff Avery Warwick

- We learn what brings him to the Cove, get the first hints of Heinrich von Nighburg’s identity and why Warwick wants him to leave

- Roy agrees to leave and take the other members of Tyson’s Nine with him but the Fairchilds sneak by into town

- Roy rallies the available members of the Nine and they make a new plan to sneak by the Sheriff

- The Fairchilds and Warwick meet when Cassandra frees a child from Nighburg’s influence

- Brandon and Cassie leverage their saving the Strathmore boy to convince Warwick to let Roy and company back into the town

- Roy and the Fairchilds reunite but before anything is discussed Nighburg retaliates, sacrificing a captured child to the Voices

- Roy and Avery get a glimpse of the mindscape before breaking Nighburg’s enchantment and ending Nighburg’s attack

- Roy and Co regroup and meet with Jonathan Riker’s son to plan their attack on Nighburg’s lighthouse

- We learn that Jonathan was the one who called in the favor Tyson’s Nine owed his father and the group makes a plan

- Strathmore joins the group and they break into the lighthouse, discovering the mirror into Nighburg’s extradimensional manse

- The manse is explored as Nighburg makes several stealthy mental attacks on them

- Nighburg slips past the town’s defenders as the Voices play havoc with their emotions and awareness

- He attempts to fulfill his ritual during the eclipse by executing Jenny Riker on the lighthouse beacon but Strathmore intervenes, dying in the process

- Strathmore’s life is enough to push the ritual halfway to completion and Roy is forced to fight Nighburg in the beacon chamber to prevent it’s completion

- When Roy throws Nighburg off the lighthouse he accidentally completes the ritual and the Voices of Taun begin to reach into the world fully

- We see the defenders of Riker’s Cove rally and hold them off for a time but their stamina wanes

- The Strongest Man in the World arrives at the last moment, the last of Tyson’s Nine, and wards off the Voices, returning the world to normal

- Characters go their own ways, with the Strongest Man warning Roy that now that he’s touched creatures from Beyond he will never be as firmly a part of his world as he was before

Since I just lay out beats in a text file and edit them as I go I don’t have a change log of the entire thing. It didn’t occur to me to save it. That said, I don’t recall very many major changes at the outlining stage. If you’ve read A Candle in the Wind, however, you can see that some elements did change between this point and the final product.

For example, many things were added, like the mayor of Riker’s Cove or Chester Tanner entering the narrative and the Statue of Jonathan Riker serving as a framing device, but the essential structure only changed in a couple of points. Tanner turned out to be related to the child Nighburg killed. That meant it made more sense for him to go into the tower rather than Strathmore – after all, Stu still needed his dad and Chester’s nephew… well, he didn’t. That change was at once important and not really that big of a deal. It required the change of one character for another but very little in the outline rested on that side character so the replacement was fairly easy to make.

By working out most of the major structural changes at the point where the entire story is less than a page of text it’s possible to check for contradictions quickly and consider the implications of changes on the broad scale without having to streamline details over and over again. This is the biggest strength of the outline.

The second thing is that there is a lot of room for improvisation and creativity between those major story beats. As I said already, the use of the statue as a framing device didn’t come around until after this step. I had all the characters and magic powers in mind before I started on this but some of the interactions, like Brandon serving as the arms of an enlarged lightbox for Johan, were things that came up on the fly. Again, some say writing an outline robs the story of spontaneity but I think that has more to do with a writer’s perception than reality.

As I said before, some authors will undoubtedly find outlining their story robs them of a drive to write it because now they know how it ends. If that’s the case for you then by all means, don’t use an outline. But if you’ve been discouraged from using one because you’ve been told you’re putting shackles on yourself I’d highly encourage you to try it once or twice. It may be just what you need to get yourself across the finish line. Tune in next week and we’ll talk about how to get from an outline to scenes.